Washington Island, Wisconsin -

Among the many men who corresponded with Thordarson over a period of several decades was Hjalmar Rued Holand.

Holand was born in Norway, October 20, 1872. His last name comes from a farming area known as Holand (with an umlaut over the "o"), in a lower part of a valley slope known as Nedre Rued (Nether Rued). He emigrated to America in 1884 with a sister, Helen, to Chicago.

He entered University of Wisconsin-Madison and earned a BA and an MA (1898 and 1899). As a young man with a history degree, he bicycled to Door County. Based on his pleasant experiences there, he soon purchased land, creating a small farm on rocky acreage in what is now Peninsula State Park. He remained an Ephraim resident the rest of his life.

Holand distinguished himself locally by writing the two-volume History of Door County, published in 1917. He served as president of the Door County Historical Society and was also active at the state level, too.

The pages of my book, Thordarson and Rock Island, begin with several paragraphs from Holand's paper titled, "A Forgotten Community: A Record of Rock Island, the Threshold of Wisconsin," published by the Wisconsin State Historical Society in 1916.

Holand was a prolific researcher and writer, with many book titles to his credit:

History of the Norwegian Immigration, 1908

History of Door County, Wisconsin, 1917

Old Peninsula Days, 1925 (many editions)

Coon Prairie, 1927

Coon Valley, 1928

The Last Migration, 1930

Wisconsin's Belgian Community, 1931

The Kensington Stone, 1932

Westward From Vineland, 1940

America 1355-1364, 1946

Explorations in America Before Columbus, 1956

It's clear from the above titles alone that Holand's interest ranged wider in scope than Door County. Much of his life he pursued the question of origin and authenticity of the Kensington Stone and the possibility of Norse presence in pre-European America. The Kensington Stone was discovered by a Minnesota farmer, Olof Ohman, a Swede, in 1898, and it was touted as one of the most important discoveries of its time. However, the stone's authenticity was challenged and discredited by certain experts.

In 1908, Holand took up the argument that it was authentic, and the stone came into his possession for a time, during which he went to great lengths to prove its validity. (Including a trip to Norway to compare it with other stones with runic inscriptions.) His defense of the stone extended to other artifacts and signs that had been discovered in the same general area of Minnesota, and also archeological discoveries in Vineland. One side story to the Kensington Stone debate was that Holand "took" the stone from the poor farmer Ohmann, and that grant had been intended only for research, to eventually turn it over to the Minnesota Norwegian Historical Society, rather than to become, or be treated as, Holand's personal property.

His books, and I must say his arguments, are intriguing even if other researchers may not consider them air tight. Holand brings forth many supporting artifacts and connections. An interesting 69-minute video on this topic can be viewed online. Search: 1362 Enigma documentary of the Vikings Arrival in Kensington

It was Holand's idea to erect a totem pole on the Peninsula State Park property in order to memorialize the woodland Indians for their way of life prior to white settlement. Pottawatomie Chief Simon Kakquados helped dedicate this totem pole, and he was buried a few years later alongside the pole on the edge of what by then had become a new golf course. This historical and cultural monument was erected, despite the fact that totem poles were commonplace in the northwest, but not on the Great Lakes area.

|

| Holand, from his book "My First Eighty Years" |

As Holand turned 90 years of age, a piece was written in the Door County Advocate by David Stevens:

"With a friendly aid from Supt. Doolittle, Holand saw a pine that had been lightly blasted by lightning and taken down. Its 44 feet of timber were then to be carved by C. M. LeSaar on lines of drawings made by Vida Weborg, and then painted with care by use of primitive color mixtures. The totem pole was dedicated on August 14, 1927. Later, at its base, was placed the marker of the friendly chief of his tribe who had shared the days of dedication with his own people and the crowd of visitors.

"The total task of creating this memorial to Indian life and the making of Chief Simon Kakquados perpetually a part of local history, by virtue of burial beside the totem pole, constitutes the most signal act for history that Holand performed, almost singlehanded. The start of the ceremonies was as taxing and important as the creative work itself. At dusk, on the day before the dedicatory ceremonies, trucks loaded with 53 Indians appeared at the Holand home south of the park. They had ridden impassively all the way from Forest County and were to be fed and housed. Pitching a hayrack full of hay from his barn, Holand then led the way down Chrystal Spring Road to a building in the Park that was to be their community shelter for two nights. He then carried out his agreements with the seven Ephraim hotels that had agreed to furnish in turn the seven meals required, free of charge, as their contribution to the gala day."

Holand died August 8, 1963 of "old age complications," according to his obituary titled, "Runestone Reader Dies."

"Curiosity about the discovery of America, and nonconformity in standing his ground, brought Holand this disputed fame. Chief encyclopedias mention neither his name nor his stone. Holand said he "spent 50 years and many thousands of dollars in travel, studying and writing to get to the bottom of the mystery."

A chapter from my book titled "Contemporaries in Door County" includes letters between Holand and Thordarson, at times a fairly regular correspondence. Each man was driven by his curiosity for local history. Thordarson was more specifically interested in the pre-European history of Rock Island.

In his letter to Holand of April 1, 1920, Thordarson wrote that he had become a lifetime member of the Wisconsin Historical Society, and he noted that "I believe you and I are the only two members of the Wisconsin Historical Society in Door County, which is a small record for Door County... I have an album, an extra copy, of pictures of Rock Island taken about ten years ago that I wish to give you."

That album, a gift of Rock Island photos taken around 1914 when Thordarson had just begun renovating old pioneer structures, found its way just a few years ago, after passing through several hands, to the Washington Island Archives. Holand so enjoyed and admired Thordarson's photos, he exclaimed, "You certainly had a fine camera."

In May of 1920, Thordarson wrote to say he was mailing several Norse-related volumes to Holand. One was a catalog of Vineland literature:

"My Islandic library is, next to Cornell, the largest Islandic library in this country and for fine bindings it is the finest that can be found anywhere. As soon as I have a chance, I intend to send those books to Rock Island and erect a library there, as we are here too crowded for space." Thordarson closed his letter with, "Hoping to have the pleasure of meeting you some time this summer…"

With their interest in local history in common, the years passed and the two continued to correspond, with Holand making arrangements on several occasions to bring Door County Historical Society members to visit Rock Island.

Despite their apparent friendliness and support of one another, on one occasion Thordarson seemed too preoccupied to show Holand the courtesy of simply writing a check, clearing any obligations he had made for the receipt of a box containing Holand's newest book, Old Peninsula Days, published in 1925.

Holand wrote that he was "scratching in every direction trying to raise enough money to pay my printing bill…I am obliged to write you to ask if you will kindly remit the amount of your bill - $130 - without delay."

Thordarson responded, "I am herewith sending you my personal check for one hundred and thirty dollars… I can only use about twenty of these books as presentation copies to my friends. The rest I will have to dispose of by selling them to someone."

This tone was not uncharacteristic of Thordarson, and it is one of the reasons why I hesitate to use the word "friends" when describing such relationships, a word connoting warmth over "acquaintance."

Access to Thordarson's Norse library would have been helpful to Holand, although we can suppose Holand had his own sources for independent research. But about Thordarson's personal opinion regarding the Kensington Stone? He was asked this by Eugene McDonald, Zenith Company president and one who was also quite interested in history of early North America.

|

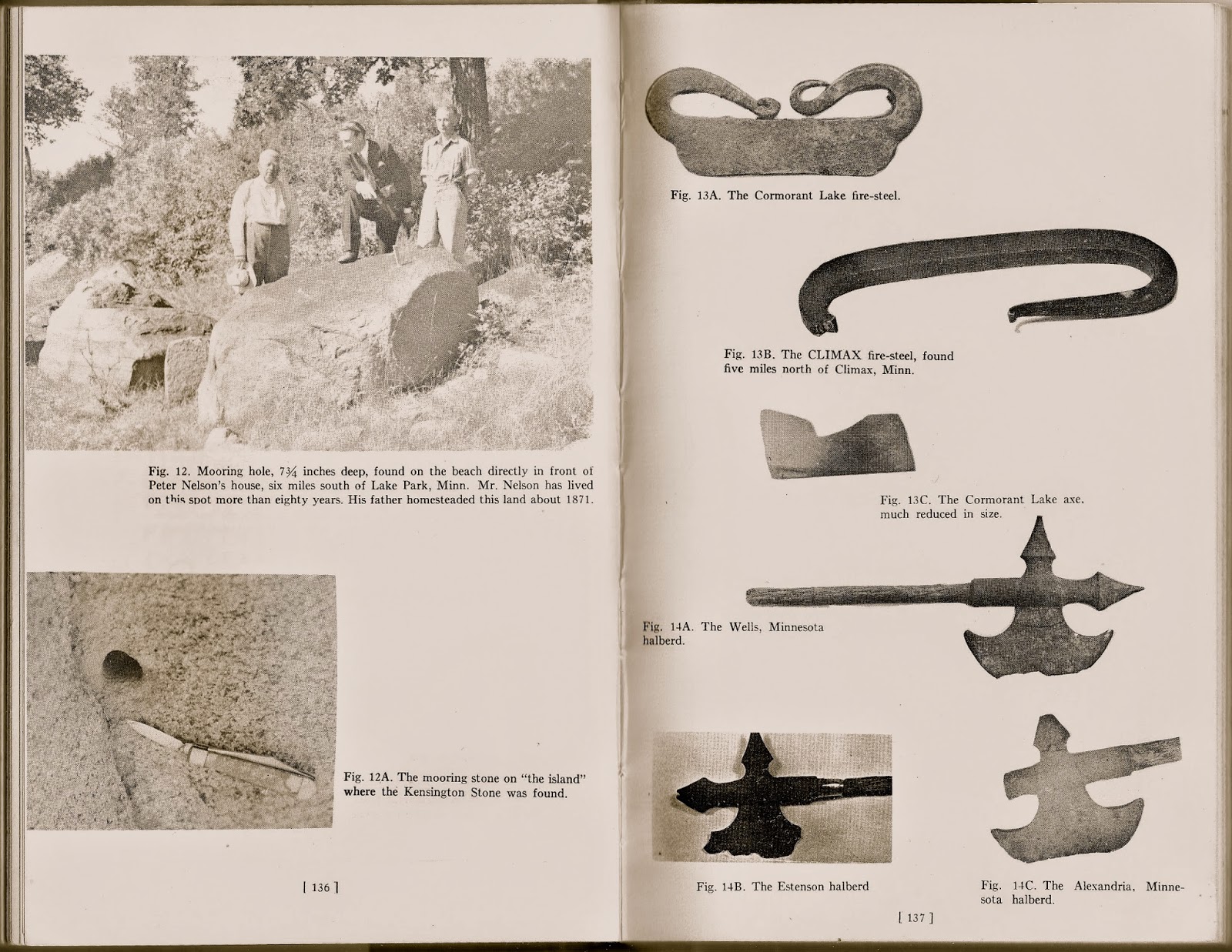

| Pages from Holand's "Explorations" book show sampling of artifacts used to support his belief in Norse presence in the 1360s in Minnesota. |

On Sept. 30, 1932, McDonald mailed Thordarson a clipping from the Chicago Sunday Times about the Kensington Stone, and he asked Thordarson, "I recall that the last time I talked with you, you still believed the Kensington Stone was not real. As I recall, one reason you gave for your statement was that there was a modern runic letter used. Do you still feel the same way?"

The manner in which each runic character was made, and the phrases that were translated, put off other experts, too, men who were critical in their dismissal of the stone being real and not a fake. Of course, Holand supplies a considerable defense of his own defending the validity of the stone, including the runic characters used, and several of his books provide platform for his arguments.

Because of his overall credibility established over a very long career, Holand has earned esteem among local and state historians. He was an individual whose traits and interests were aligned in many ways with Thordarson. At the very least, Holand's books make for entertaining and informative reading.

The Sons of Norway Lodge of Sturgeon Bay, Wisconsin, is named the H. R. Holand Lodge.

- Dick Purinton

No comments:

Post a Comment