|

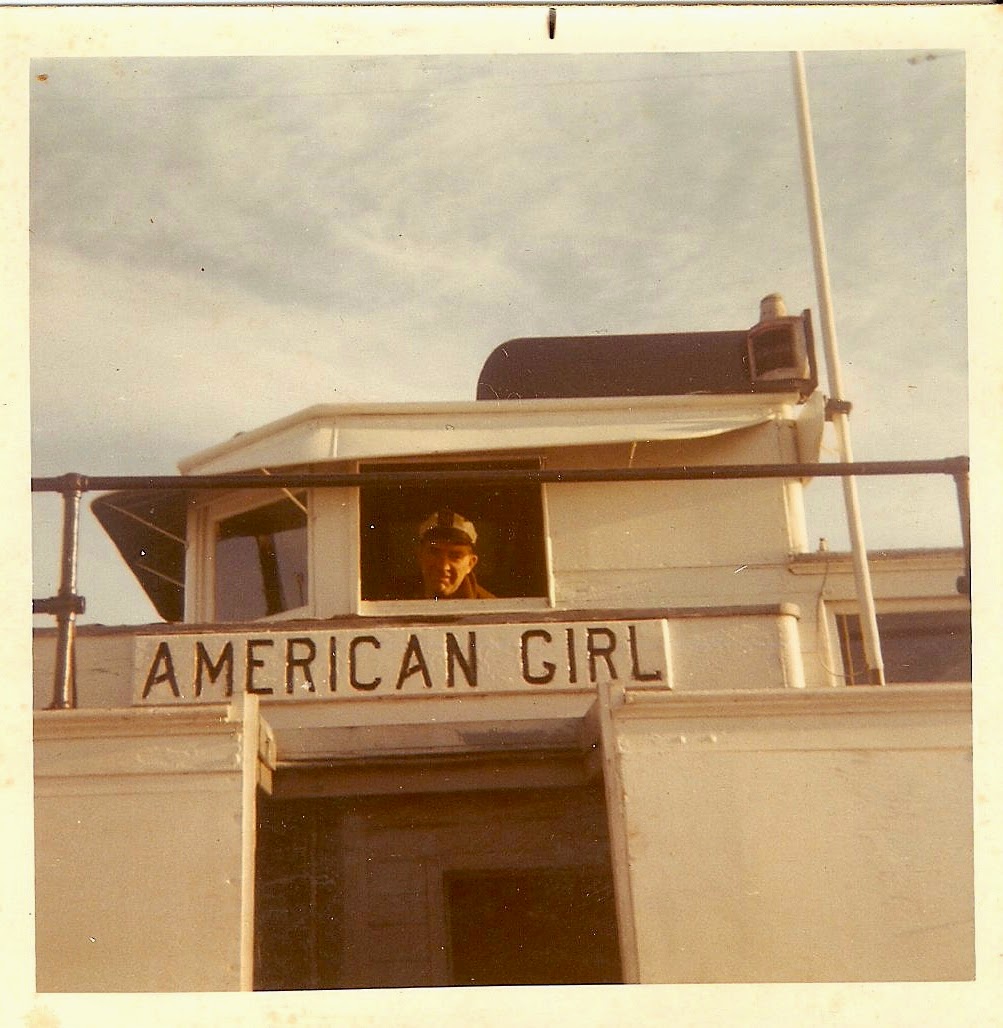

| Cecil Anderson in wheelhouse of American Girl. |

Washington Island, Wisconsin -

We mentioned the unfortunate loss of the Lawrie boat North Shore when it sank in 1930, taking the life of Ervin Anderson, his wife, Harriet, and four others. The Anderson family experienced another tragic loss a few years later when the youngest son, Elliot, drowned. The July 22, 1932 Door County Advocate (DCA) carried the story:

Struck by lightening and tossed into Lake Michigan from the rowboat in which he was riding in tow of his father's small freighter, Diana, midway between Plum Island and Detroit Harbor, Elliot Anderson, 14, son of Capt. and Mrs. John Anderson of their place, was instantly killed or drowned after being knocked unconscious Wednesday afternoon about 3 o'clock.

About ten motor boats and rowboats, including three from the Plum Island Coast Guard station in charge of Capt. Mattie Jacobson, went to the scene to aid Capt. Anderson in the search for the body which was brought up by the father by means of a couple of trout hooks on a long line just before dark. The water in the passage at the point of the drowning was about 60 feet deep.

The Diana with Capt. Anderson, his sons, Cecil and Elliot, and Haldor Gudmundsen, Standard Oil Company representative here, went to the Plum Island Coast Guard station early in the afternoon Wednesday with a load of oil. They were on the return trip, half way across the two-mile wide passage, when the thunderstorm struck, accompanied by a slight squall. The bolt that hit Elliot first struck the stern light post. Part of the charge glanced into the row boat and the balance went up an aerial, snapping off the wire which fell to the deck and hit one of the men but without serious consequence.

Coroner Elmer Christenson of Sturgeon Bay was notified of the death by William Jess, chairman of the township, and authorized the latter to act as his deputy in the case. No inquest will be held.

Elliot was born here and was a graduate from the eighth grade of the Detroit Harbor School. He is survived by his parents, two brothers, Cecil and John Jr., and seven sisters, Myrtle, Florence, Beatrice, Genevieve, Effie Belle, Edith Jane and Mary Anne. The funeral will be held Saturday from the home and the Lutheran Church her with the Rev. John Christianson officiating.

Despite these setbacks, events that surely changed their lives, the Andersons' freighting continued - the process of loading, unloading, tracking orders and billing, not to mention departing in a wooden vessel at a time when weather forecasting was based mostly on a barometer. By the time World War II ended, Washington Island's freight volume had increased - or at the very least, it was being carried by a couple of remaining wooden freighters. Business demands, and the age and capacity of the Diana, led to the purchase of the American Girl in 1947.

It was far from being a new vessel, having been built by DeVoe in Bay City, Michigan in 1922, but it had been well cared for. Compared with the older, wooden boats, the steel-hulled American Girl was spacious, with good load capacity, good power, and it was fully enclosed for operating in much harsher conditions, including colder seasons of the year.

When the Washington Island Electric Co-operative started up its diesels in 1946 in order to energize Island homes and businesses, fuel was consumed by either one or two diesel generators that ran 24 hours a day. With competition from other freighting outfits gradually lessening, by the early 1950s the Andersons and the Ferry Line remained as the only carriers of freight. Bulk orders for the Island's groceries still came direct from Green Bay aboard the American Girl, as did lumber and building materials, kegs of beer, cases of soda pop, tires and automotive parts, and for Island homes still dependent on coal as heating fuel, loads of coal.

The labor expended to load and unload seems staggering when compared with today's mechanization. For instance, transporting coal began when a C. Reiss Coal Company truck would back up to the American Girl at the Green Bay landing and dump its load down a chute into the boat. The Andersons then unloaded at the Island using a large bucket, winch and hooks. Later on, Cecil asked Clyde Koyen to fabricate a mechanized conveyor system that brought in freight through a side door, a labor and time saving device that made the crew work more rapidly to keep up with the conveyor's pace.

Trips leaving the Island often consisted of empties: beer kegs, pop and beer bottle cases, and empty petroleum barrels. This was a time when lube oil and gasoline was still transported by individual barrels. This latter operation brought special concerns, that bung plugs on the barrels might be loose and leak product into the bilge, with the potential for an explosion.

Once the Ed Anderson potato farm operation was in full swing, in the closing 1940s, potatoes became a seasonal product shipped in the fall to Sturgeon Bay and also Escanaba. The American Girl as well as other Island vessels unloaded potatoes from vessel to box car at those ports. Herring, caught by the ton in the early 50s, also required special runs, usually to Menominee, Michigan. These special, seasonal runs were quick, turn-around trips, sandwiched into the schedule so that the regular Island run to Green Bay for fuel and freight could be maintained. In a typical week, the Andersons might enjoy one day at home, a Sunday, with the rest of the week consisting of long days spent either loading or unloading, or in transit between ports.

Following are descriptions of the American Girl freighting operations in Jim Anderson's words:

Hauling coal:

At that time, we also hauled a lot of coal, as many homes

had coal furnaces then, so we would usually haul most of that in late summer

and early fall, in preparation for the winter months. This was delivered to us bulk by a truck in Green Bay from

the C. Reiss Coal Co. They would

bring a dump truck load of whatever coal was ordered, such as briquettes or lump coal, and then they dumped it down a coal chute, in to the hold of the

American Girl. We, in turn, would

unload at the Island with a big, hinged bucket which would be lowered down into the hold of the boat via

the boom and winch. The bucket would be filled by two of us shoveling the coal

into the bucket and, in the case of

large, lump coal, simply picking up pieces and placing them in the bucket.

When the bucket was filled, the winch operator on deck would

get the signal to lift it up, and

when it cleared the hatches and gangway it was pulled to a waiting truck by a

rope attached to the boom. Then, the

trucker would position the bucket where he wanted it dumped on the truck, grasp

it by the bottom, turn it on its hinge and dump it. Then he would right the bucket and push it backwards toward

the opening of the hold, stopping it with the rope on the boom. The winch man would drop it down to the

deck of the hold, and the process would start over again. In this way, we also roughly figured

the weight of the coal, so much per type of coal per bucket. So if the Reiss Co. brought us 20 tons

of coal, it might be going from two to four different customers on the Island,

so if, say, Nelson Bros. had five tons ordered, they would get the right amount

of buckets to approximate that weight.

The trucker would then deliver that load to the customer and then return

for another load.

Hauling fish:

In the 50s, there was also a lot of commercial fishing here

and the American Girl was used to haul herring to Menominee, Michigan, when the

herring run was on. We also used

to haul wood fish boxes which were made at M & M Box Co. in Menominee. There were brought back to the

fishermen on the Island to be used by them. I remember going on the American Girl when I was

pretty young, after a load of fish boxes.

My dad always would take me to the box factory there by the river, and I

can still remember the wonderful wood smell of that box factory. It was there that I saw my first

pop machine, one of those that had the ice water in it and the bottles of pop

hung suspended on a rack in the very cold ice water. I can still remember my dad taking me there and putting a

nickel in the slot and fishing out an ice cold bottle of orange soda for

me. It was wonderful.

Transporting potatoes in the fall:

Another major cargo at that time was potatoes. In the 50s, Ed Anderson’s potato farm

was in full swing, and it produced approximately 250,000 bushels a year. All those potatoes had to get to market

by boat, and the American Girl hauled a lot of those potatoes. Also, the Washington Island Ferry Line

used the ferry Griffin, and Chris Andersen hauled some on his 65-foot hooker, Wisconsin.

In the early days of the potato harvest, the method was hand-picking into baskets which were dumped into a bulk wagon, and then bagged back

at the farm. The weight of the

bags was approximately 100 lbs.

The bags were transported by truck and wagons to the American Girl,

where 1100 of those bags were loaded on to the conveyor system into the hold of

the boat. The hold was filled from

bottom to top, utilizing every inch of space, and when the hold was filled the

hatches went on and the deck and gangways were then piled full. When she was all loaded, the only way

into the boat was through the top of the pilot house connecting

hatch. Then the gangways were put

in and doors pulled shut and she was pretty well closed up. They were then hauled to Sturgeon Bay

and loaded by conveyor into the railroad

cars. During the peak of the

season, the American Girl would make a trip a day with a load of potatoes to

Sturgeon Bay. They would to this

for a week or so with a break in between to make a run to Green Bay for a load

of gas and oil and groceries and other cargo needed on the Island – then back to

the potato run again.

On hauling fuel and lube oil, before the Oil Queen:

When she first got here, the American Girl hauled whatever

my grandfather and father could find to transport. At that time, they hauled all the oil and gasoline to

the Island in 55 gal. barrels.

They were loaded into the hold of the boat with the winch and boom and

barrel hooks, and they were unloaded the same way on the Island. They were then pumped out into storage

tanks which Standard Oil Company had here on the island. Then, all the empty barrels were

transported back to Green Bay.

This was a lot of work and danger, especially with gasoline

and the greatest fear was that of a barrel with a loose bung might create a gas

leak and an explosion in the hold of the boat. At that time, they also hauled coal, groceries, fish or

anything that had to be moved.

In 1949, the Standard Oil Co. and my father and grandfather

could see a need for a better way to transport oil and gas to a growing Island

community, and so they had a 65-ft. steel tow barge built in Sturgeon Bay,

Wisconsin, by Christy Corporation.

She was named the Oil Queen and held 28,000 gallons of

product. Then the need for barrels

was eliminated and fuel was bought bulk except for lubrication oil. The American Girl was repowered by a

Caterpillar diesel engine and fitted with a winch in the aft cabin to tow the

barge. The winch held 600 feet of 1” cable, and usually the barge was towed

approximately 550 feet behind the American Girl.

|

| For many years, two phones for two different phone systems were used, one for the Island (above) and one for Green Bay (below). |

|

| Jack Anderson, on the phone about a freight order. |

So as the Island's economy started to

grow in the early 50s, so did the amount of freight coming to the island. My grandfather by now was a bit older

and his youngest son, Jack, took

over his ½ of the business, and he and my father became partners in 1955, and

from then on it was called Anderson Transit Co.

On navigation before electronic devices came along:

Navigation equipment in those days on the American Girl

consisted of a compass and an alarm clock. You ran your courses on times and factored in other

circumstances. They didn’t have

such things as radar, loran or GPS.

In fact, I can remember how excited dad was when they got a fathometer,

and then later, a ship to shore radio. My father then was the pilot and navigator, and my

uncle Jack oversaw the engine room.

My dad had started sailing with his dad full time when he was 12 years

old, and of course he became quite experienced after all those years. After they got the fathometer, my

father kept track of all the depths wherever they went and kept all info in a

logbook along with his courses and times, to run from one checkpoint to the

next checkpoint. All weather

condtions were kept track of and noted down as they all could have effect on

the course your were sailing.

|

| Launch day for the Oil Queen in 1949 at the Christy yard, Sturgeon Bay. (Herb Reynolds photos) |

The Andersons' investment in a new oil barge was helped by the Standard Oil Company, which awarded them with a contract to fill tanks at a Sturgeon Bay waterfront location. The loaded Oil Queen would sometimes moor in Sturgeon Bay, leaving Jackie on board, who then pumped off the product while the American Girl headed north with freight - which often included perishables. Jackie would then hitch a ride to Gills Rock or Northport and arrive at the Island in time to help unload.

Business was steady in the 50s and 60s, with a general progression in freighting. There was the steady requirement to supply the diesel, gasoline and heating oil needs of the Island. But, there was the extra work and concerns brought on with towing the oil barge.

After the Washington Island Ferry Line brought on a new ferry in 1970, the Eyrarbakki, and converted the C. G. Richter to a single screw for winter ice work, the Andersons bought the Griffin in late 1971. Then, they converted the Griffin from an auto / passenger ferry to a tanker at the Palmer Johnson Boatyard in Sturgeon Bay, and for the 1972 season the Griffin took over the freight runs carrying both deck freight and oil products in the tanks.

|

| Griffin as a tanker passing through Sturgeon Bay's Michigan Street bridge in 1973. |

With the Griffin then handling oil products, the American Girl and Oil Queen barge were sold to a Beaver Island man, Jewel Gillespie, who continued with the pair of vessels, supplying Beaver Island's needs. Although the Oil Queen no longer is used today, the American Girl is still operating, refurbished and repowered, still under the same name. It tows freight barges, and the owners take on other towing opportunities, but its run is mainly between Charlevoix and St. James Harbor, Beaver Island, Michigan.

The Griffin then continued to serve Anderson Transit's freighting needs until 1974. Jackie Anderson died of cancer that year. Cecil had turned 62, and he considered selling. Son, Jim, was back from serving in the U. S. Air Force, and in 1972 he had started a sporting goods retail store near the family pier, the Island Outpost.

Cecil and Cynthia, Jackie's widow, sold the Griffin to Jon and Lois Gunnlaugson, who continued to operate it as a tanker / freighter for approximately ten more years. During that time, the manner and timing of supplying oil products began to change, with greater emphasis on stocking up in the late fall, rather than gradually over summer and fall. This brought added pressure on the operator requiring more trips in the worst season of the year.

|

| Griffin, around 1980, wintered at Standard Oil pier. (Purinton photo) |

Meanwhile, the Ferry Line's several open and flat-decked ferries were considered for hauling Amoco gasoline and diesel products, and soon bulk tanker trucks were scheduled, hauling product direct from the terminal in Green Bay to the Island bulk plant via ferry.

Groceries and other bulk items, too, such as lumber and cement, general merchandise that was a part of the freighting income that supported the Griffin's operation, were likewise shifted to trucks that delivered directly to, and unloaded at, the premises of Island dealers.

The Griffin was sold in 1985 to Chicagoan Glen Dawson, who converted it from a tanker back to a passenger vessel and used it for dinner cruises and sightseeing in the Chicago harbor area.

From 1984 onward, nearly all freight consigned to Washington Island arrived by ferry, either on deck, by trucks that were driven onboard the ferry, or carried in smaller volumes in the vehicles of Island residents and business owners.

- Dick Purinton (With thanks once again to Jim Anderson for the many photos and information.)

.jpg) |

| Jackie and Cecil with the Oil Queen. |

|

| American Girl and Oil Queen at Standard Oil dock - 1950s. |

|

| Recent photo of the American Girl. More information can be found on the website http://www.stjamesmarine.com/american-girl/ |

1 comment:

All of these postings are terrific Dick. Fascinating reading. And the American Girl at 93 ...... amazing!

Post a Comment