Washington Island, Wisconsin -

We continue with the story of the Richter ownership and operation of the Ferry Line, now in its 75th year in this year, 2015.

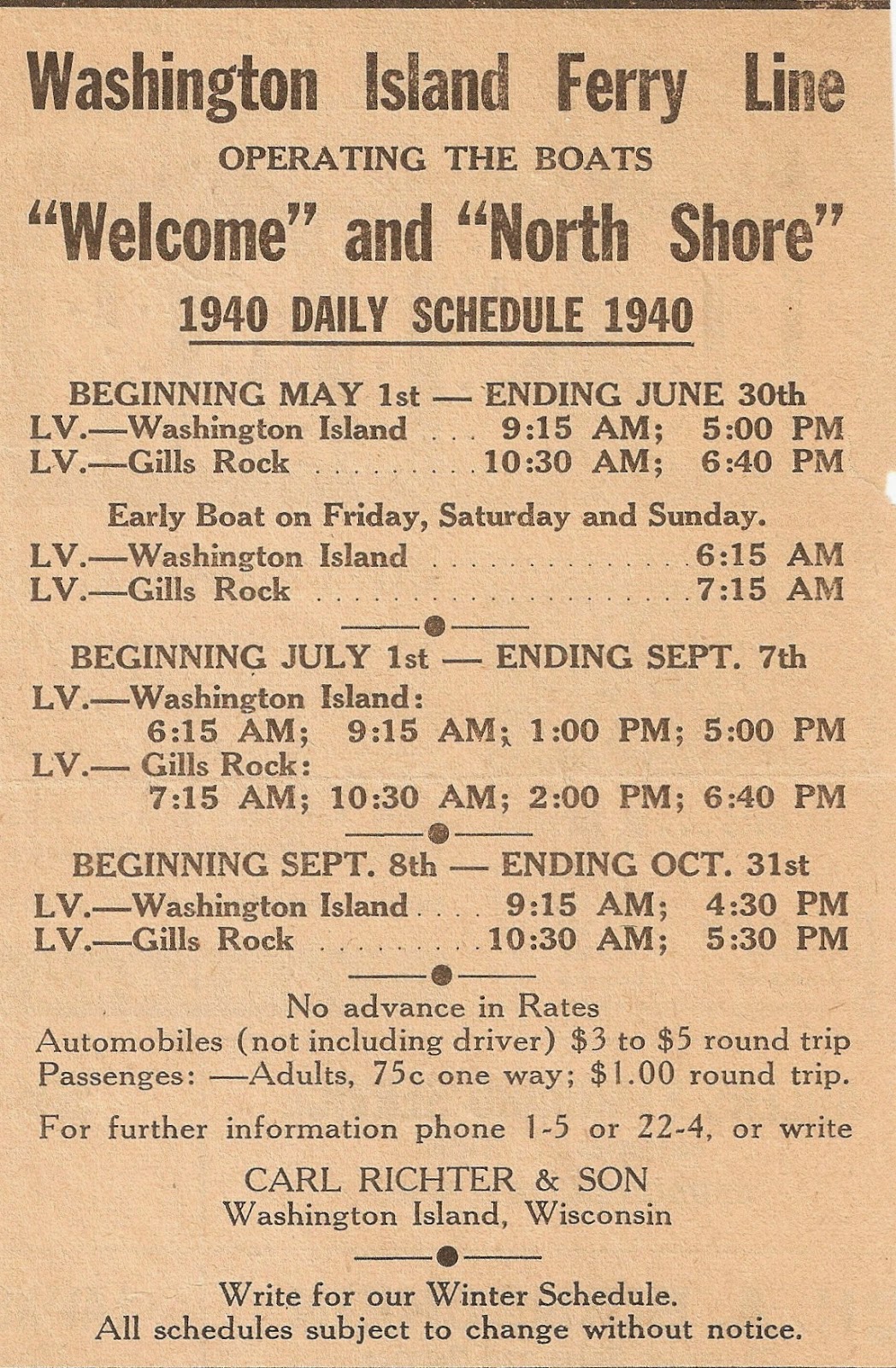

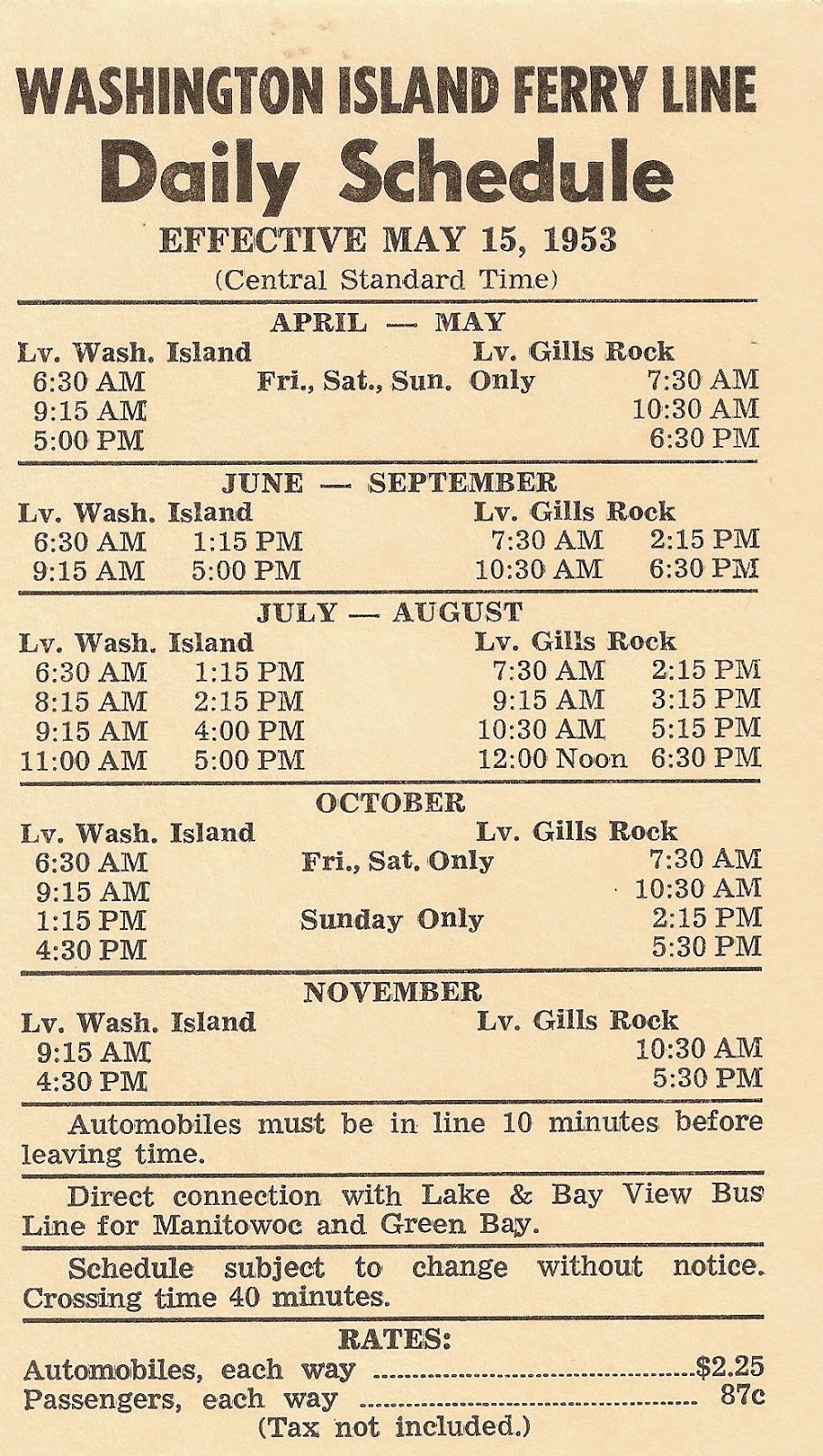

The schedule comparison shown above is interesting for a couple of reasons. For one, there was deference paid to Carl in 1940, with credit paid to "Carl Richter & Son." This would soon change, and maybe it was more practicality than anything, acquiring a business name that would be readily associated with Washington Island. But over time it was still the Richter name, Arni Richter's name, that would be closely associated with Island ferry service, and in a general sense, with Washington Island as a whole. Arni's involvement in the Door County Chamber of Commerce, his role as a director for the Bank of Sturgeon Bay, and his staunch support of the Republican Party (that brought him in contact with several Republican governors, state legislators, and Congressional representatives) held both social and business implications for the Richters and the Ferry company.

The schedule comparison shown above is interesting for a couple of reasons. For one, there was deference paid to Carl in 1940, with credit paid to "Carl Richter & Son." This would soon change, and maybe it was more practicality than anything, acquiring a business name that would be readily associated with Washington Island. But over time it was still the Richter name, Arni Richter's name, that would be closely associated with Island ferry service, and in a general sense, with Washington Island as a whole. Arni's involvement in the Door County Chamber of Commerce, his role as a director for the Bank of Sturgeon Bay, and his staunch support of the Republican Party (that brought him in contact with several Republican governors, state legislators, and Congressional representatives) held both social and business implications for the Richters and the Ferry company.

Another interesting comparison is found in examining the rates, where one-way passenger fares ($1.00 in 1940 vs. 87 cents in 1953) and auto rates were actually less in 1953 than in 1940. Perhaps increased volume had something to do with those rates, but in 1953 there were two, relatively new ferries, Griffin (1946) and C. G. Richter (1950), still working off construction debt. Farming and fishing were then two booming Island industries, with dairy and potato farming continuing apace, and commercial fishing was the king industry in terms of incomes and steady employment. Those industries translated to a great deal of freight hauled, meaningful in terms of revenue for both the Anderson Transit Co. and the Ferry Line. Perhaps the freight revenues helped to meaningfully support the business overall.

The construction of the Voyageur in 1960 departed from the side-loading ferries that required wooden planks (later replaced by a steel plate) to span the gap between vessel and shore. Although the Voyageur had only a single ramp, located in the bow, loading could be accomplished quickly by directing drivers and backing autos on board. A creative crew with the right mix of traffic could load a dozen vehicles in a short time. Oftentimes, the load was a mix of autos, trucks and trailers, and occasionally large equipment that earlier ferries simply were unable to carry.

By 1970 traffic justified a second open-deck ferry, an even longer vessel named Eyrarbakki. If the Voyageur had been a grand improvement for carrying vehicles of all sizes, the Eyrarbakki went one better. She had both a bow and stern ramp, and rather than the restrictive open deck of 50 feet of the Voyageur, at 87 feet LOA the Eyrarbakki had approximately a 70-foot opening, making possible the loading of just about any combination of truck and trailer that could be brought over the bow. (Eyrarbakki still has the largest unrestricted height, open deck space of all of the ferries.) Standard vehicles (if they required less than a 9-foot overhead clearance) could be easily loaded in a drive-on, drive-off arrangement, and overall capacity came to 18-20 autos. There were still large "Detroit boats" being driven for comfort rather than concern for fuel prices in those days, but new, smaller Japanese models had joined the highway mix, plus Detroit's "compacts" that provided options for crews to load an extra car here and there, maximizing usable deck space on a busy day.

With a new ferry C. G. Richter in 1950, another in 1960 (Voyageur) and a third in 1970 (Eyrarbakki), there came a public tendency to believe that a new ferry would be built "about every ten years." Pushing this theory along (and based solely on the coincidental rise in tourism and the need to keep pace with summer traffic, not a pre-ordained circumstance) was yet another ferry designed and built for launch in early 1979.

The Robert Noble's design would enlarge, slightly, upon the dimensions and capacity of the Eyrarbakki, and in so doing it would render the C. G. Richter less useful - almost obsolete - as a summertime vehicular ferry.

The answer, in order to get use from an aging vessel that still had many nautical miles left under her keel, was to convert the C. G. to summer passenger-only use.

By 1984, an extension of 70 feet had been made to the Northport Pier, and as a result Gills Rock became a "passenger excursion" port, with the C. G. competing in summer, first with the Yankee Clipper, owned by Charles Voight, then after 1987, with Voight's new, aluminum Island Clipper.

One fact of business Arni liked to recite was that each new ferry exceeded in cost the sum total of dollars spent on all previous ferries. This reflected not only the nature of new construction, with increased complexity in safety equipment and design features intended to meet U. S. Coast Guard regulation, but also the tendency to improve each new ferry in size and utility. With increased size came increased horsepower, and larger transmissions, all with added cost. Each new construction contract was supported with the optimism that it would prove to be the right decision, and that a new ferry would help to sustain, if not increase, business for the Ferry Line and the Island.

Adding to the "ten year cycle" myth circulating in Door waters would be yet another ferry, Washington, also built by Peterson Builders, Inc., this one designed start-to-finish by Tim Graul Marine Design (TGMD). It should be noted that during this period, Peterson Builders was attempting to transition from a heavy dependency on U. S. Naval contracts, which were becoming harder to obtain, while at Bay Shipbuilding nearly all shipbuilding efforts were going into the large commercial ship construction or repairs for the laker fleet. Bay Ship didn't seek new, small vessel construction at this time, although that approach would change again in time.

The Washington's design was a departure from previous ferries, most notably for the use of a center pedestal, or trunk, that supported a substantial superstructure. The Washington had greater length and beam (100-ft. x 37-ft.) than previous ferries, but the increased overall dimensions, as it turned out, were somewhat offset by cramped lane conditions alongside the trunk, which incorporated public heads, engine room and passenger deck access stairs, piping and wiring runs, and light cargo storage.

Every vessel results in compromises, however, and overall, this ferry became a summertime savior by taking on long lines of vehicles and passengers, loading them with ease. In certain instances, she's also been used in the freeze-up stages of December, having good sea keeping abilities, with less propensity to toss spray over the deck. But, summertime use was its main purpose, to meet with the still-increasing patterns in traffic. The 1990s, with dot.com financial bubbles not yet ready to burst, also brought increasing tourism, very much on the rise in Door County as a whole. This ferry, Washington, coupled with a new break wall built in 1994 that surrounded the Northport dock and made landings much less subject to wind and waves, became a very useful piece of equipment.

Every vessel results in compromises, however, and overall, this ferry became a summertime savior by taking on long lines of vehicles and passengers, loading them with ease. In certain instances, she's also been used in the freeze-up stages of December, having good sea keeping abilities, with less propensity to toss spray over the deck. But, summertime use was its main purpose, to meet with the still-increasing patterns in traffic. The 1990s, with dot.com financial bubbles not yet ready to burst, also brought increasing tourism, very much on the rise in Door County as a whole. This ferry, Washington, coupled with a new break wall built in 1994 that surrounded the Northport dock and made landings much less subject to wind and waves, became a very useful piece of equipment.

|

| Washington set to depart. Crew: (L to R) Jeff Cornell, Laura (Shellswick) Lerner and Erik Foss. |

The age of the C. G. Richter, having design qualities unacceptable to owners of longer and higher vehicles, and with increased bulk freight demand in the dead of winter (fewer Island goods were being stockpiled in advance, with less small package freight), and without the mass and horsepower to bull through frequently encountered ice conditions, and with its less-than-adequate passenger accommodations (both heads and cabin space) her days were numbered.

But, it would take substantially more capital, plus the right design - whatever that might be - before a contract would be signed for a new winter ferry. That timing proved to be 2002, a decision that followed much internal discussion and regular, annual deposits into a construction fund. By that time, Arni Richter had retired (after making an official retirement statement, but one not always heeded!), and the new ferry to bear his name would have greater size, horsepower, and capacity than any of the other ferries. And as before, it would result in greater expense than all previous ferry vessels combined!

But, it would take substantially more capital, plus the right design - whatever that might be - before a contract would be signed for a new winter ferry. That timing proved to be 2002, a decision that followed much internal discussion and regular, annual deposits into a construction fund. By that time, Arni Richter had retired (after making an official retirement statement, but one not always heeded!), and the new ferry to bear his name would have greater size, horsepower, and capacity than any of the other ferries. And as before, it would result in greater expense than all previous ferry vessels combined!

The Arni J., as this ferry quickly became known, at 104-ft. LOA could carry 18 vehicles with ease, having broad vehicle lanes nearly 10 feet wide, with passenger cabins and passenger deck access, heads and engine room access offset in a structure along the starboard rail, giving it capability to carry several semi trucks by driving them straight through - this ferry came to be a considerable improvement for winter and summer ferry service.

|

| Capt. Bill Jorgenson at wheel of Arni J., in ice. Hull speed is a consistent several knots, even in solid ice 10' thick. |

Best of all, as it turned out the Arni J. exhibited wonderful icebreaking capabilities. This was due, in no small part, through copying the lines of the successful design of the most recent Drummond Islander ferry at Point DeTour, Michigan, also designed by TGMD. A flight to Drummond Island in a small plane piloted by Graul convinced Arni there just might be a new and better design possible, rather than repeating or enlarging the C. G. Richter design. (At one point, several years earlier, Arni had stroked his chin while he mused, "I don't think you'll ever find another design as good as the C. G. Richter for winter work!")

If Arni hadn't entirely agreed with the general design and parameters for the new ferry as they were developed with Tim Graul's expertise, he did go so far as to agree to put his name to it, and then to strike the bottle of champagne against a gangway upright when the moment for public approval was ripe. His oft-repeated statement at age 92, and later, and not without intended humor, was: "If my name's on it, it better be good!"

- Dick Purinton

1 comment:

Though the honor accorded Arnie was well-deserved, it is traditional for a lady to be the Godmother of the ship. You may need a second christening be install Mary Jo as the Godmother. I would be happy to perform the MC duties at a re-christening ceremony in September, thereby killing two birds with one stone.

Kilpela

Post a Comment